About Tommy Thompson Park

Our Story

One of the most interesting characteristics of Tommy Thompson Park (TTP) is that the land on which it lies is completely man-made.

Since the Toronto Harbour Commissioners (THC) initiated construction, millions of cubic metres of concrete, earth fill and dredged sand have been used to create a site that now extends about five kilometres into Lake Ontario, and is 500 hectares in size.

HOW IT ALL STARTED

In 1959, THC (now PortsToronto) began the construction of the Leslie Street Spit (or Outer Harbour East Headland) for “port-related facilities.”

In the years between 1974 and 1983, the land base dramatically increased, as approximately 6,500,000 cubic metres of sand/silt were dredged from the Outer Harbour and placed at the spit. This resulted in the formation of the lagoons and sand peninsulas which now account for a significant proportion of the land base of Tommy Thompson Park.

In 1979, another major expansion of land area took place, with the construction of an endikement on the lakeward side of the Headland. This provided protected cells for dredged material from the Inner Harbour and the Keating Channel.

AN “ACCIDENTAL WILDERNESS”

In the early 1970s, it was clear that a site for port-related facilities wasn’t needed. By this time, however, the natural processes that had evolved during the planning and construction of the site had shaped the spit into a truly “accidental wilderness.”

In August 1973, the Province gave Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) “the responsibility of being the Province’s agent with regard to the proposed Aquatic Park [Tommy Thompson Park] and the preparation of a master plan”. In 1977, this was expanded to include not only the preparation of a master plan, but also development and interim management — including public access, nature interpretation and wildlife management.

The park is named in honour of Toronto’s first Commissioner of Parks, Tommy Thompson. He was influential in the design and development of Toronto Island Park and worked to protect Toronto’s ravines by keeping them as “wild” as possible.

Public access to Tommy Thompson Park is restricted to weekends, holidays and weekdays from 4 pm to 9 pm, due to the truck traffic associated with the Port Authority’s ongoing filling operations. Nevertheless, more than 100,000 visitors enjoy Tommy Thompson Park every year. This “accidental wilderness” is now widely recognized as one of the best areas for greenspace improvement along the Toronto waterfront.

TOMMY THOMPSON PARK: A TIMELINE

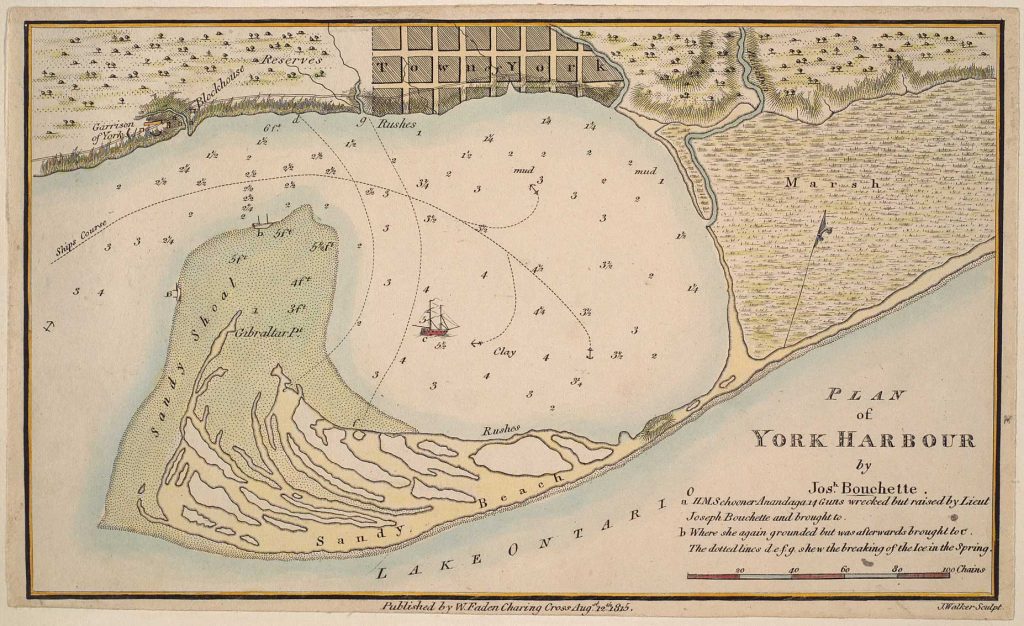

Europeans are settling and developing present day Toronto. The Don River flows into Ashbridges Marsh, one of the largest freshwater marshes on the north shore of Lake Ontario. This marsh is home to birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians and fish.

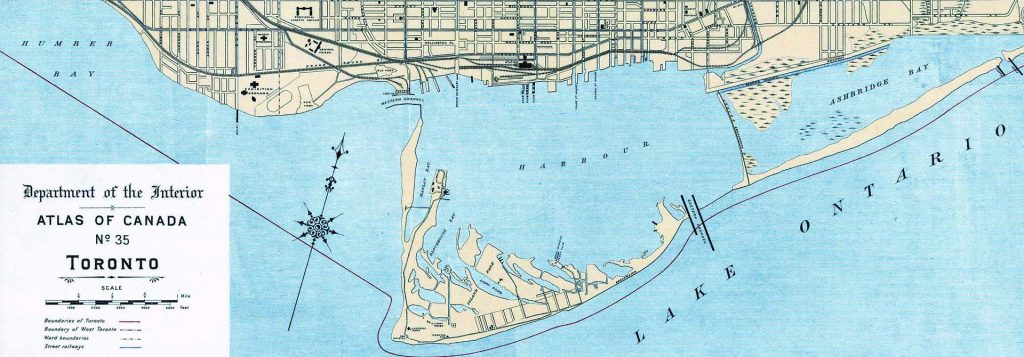

Urbanization continues in the Toronto harbour. Hard to imagine today, it was very mucky and dirty. Gooderham & Worts Distillery establishes on the bank of the Don River, a booming distillery business along with cattle feedlots. Waste is disposed directly into the river and Ashbridges Marsh. The environmental conditions in the marsh are declining and by 1911 a decision is made to fill the marsh to create lands that will serve more economical purposes.

Filling of Ashbridges Marsh is mostly complete; the marsh habitat is long gone.

The Baselands are constructed first, followed by the start of the ‘Spine Road’ (i.e. Multi-Use Trail). The fill material in these areas is made of brick and concrete rubble from demolition and construction sites across Toronto.

The peninsulas and embayments are created through a hydraulic dredge of the outer harbour. They are made of the sand-silt material from the lakebed that provide a different growing medium than the rest of the landform. Port activities have not taken off as anticipated in the late 1950s. The provincial government awards Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) the responsibility of developing a Master Plan for a public park on the lands.

With the binational Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement of 1978 new regulations were put in place for a minimum quality of material that could be disposed of in open water. Dredged materials from the lower Don River and Keating Channel did not meet these regulations, and as such, construction starts on three Confined Disposal Facilities that will permanently hold the contaminated sediments.

Trees and shrubs are establishing on the peninsulas. The Confined Disposal Facilities are built and the north cell, Cell 1, is filled to capacity. Lakefilling continues south of Cell 3.

The landform is nearing its final footprint. Lakefilling continues on the lakeside, north of the lighthouse to create the Toplands.

Lakefilling is complete. Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) has implemented Master Plan phase I including habitat creation and enhancement projects, trails and buildings. The park is designated as an Environmentally Significant Area and an Important Bird Area. It provides critical habitat for wildlife and unique recreation opportunities minutes from downtown Toronto.

Master Plan

The Tommy Thompson Park Master Plan is the long-term vision for Toronto’s Urban Wilderness. It aims to create, enhance, restore and protect the natural features of the manmade landscape while providing recreational opportunities for all.

Preserve significant species

Protect environmentally significant areas

Enhance aquatic and terrestrial habitat

Enhance public recreational opportunities

Habitat Restoration

Toronto and Region Conservation Authority (TRCA) is an industry leader in habitat creation and restoration.

The ecological approach to Tommy Thompson Park development has been guided by the principles of “Conservation by Design”. This is defined as the purposeful act of designing for a variety of natural habitats while combining natural succession principles to create functional, productive areas.

The goals of restoration work at Tommy Thompson Park are to preserve significant species, protect environmentally significant areas and enhance aquatic and terrestrial habitat. This approach integrates a variety of wildlife habitats and areas of natural succession to create functional habitats.

What may look like disruptive construction is actually providing a key ecological concept! Construction equipment that manipulates the landscape creates a diverse topography with different growing conditions and provides the foundation for a natural variety of potential habitat types. This in turn encourages the natural succession of plant communities.

Wildlife

From its origin as rubble and sand, Tommy Thompson Park has developed into a complex mosaic of habitats, which support a diverse community of flora and fauna species.

The complex of plant communities found at Tommy Thompson Park, as well as the rare and significant plant species, are a result of the highly variable soil of the site. Because the site was created through the dumping of construction residues, soil fertility and composition can vary dramatically within very small areas.

The area’s diverse biological communities and location on Lake Ontario make it an important stopover point for migrating birds, butterflies and other insects. These communities also attract breeding birds and insects, which make the park seem to “hum” during the summer months.

Due to the nature of construction and substrates, Tommy Thompson Park is quite impervious to water infiltration. The consequence is standing surface water that creates seasonally wet areas that are highly attractive to a variety of wildlife. These seasonally wet areas are heavily used by migratory shorebirds and as nesting sites for regional and locally rare bird species such as Virginia Rail, Sora, and American Woodcock. Seasonal pools are also important breeding areas for amphibians

Although the upland areas do not currently support a great variety of amphibians, as the wooded communities mature the park has the potential to be one of the few locations across the waterfront capable of supporting woodland dependent amphibians such as spring peepers, woodfrogs and salamanders. The cottonwood forest at Tommy Thompson Park provides habitat for tree nesting colonial birds, forest dependent songbirds and various small mammals among many others.

The complex shoreline and nearshore areas of the park provide habitat for warm and cool water fish, invertebrates, amphibians, waterfowl and wading birds to name a few. Wetland enhancements will continue to improve the suitability of the habitat for a range of other wildlife species.

The ecological value of Tommy Thompson Park will continue to increase dramatically as the habitat communities mature, and as the lands are enhanced through new and continuing restoration projects.